First impressions of Jurassic World Rebirth — and my complicated history with dinosaurs

Gareth Edwards's new film in the classic Spielberg franchise has rekindled troubling memories of my childhood obsession with dinosaurs.

My relationship with dinosaurs is complicated.

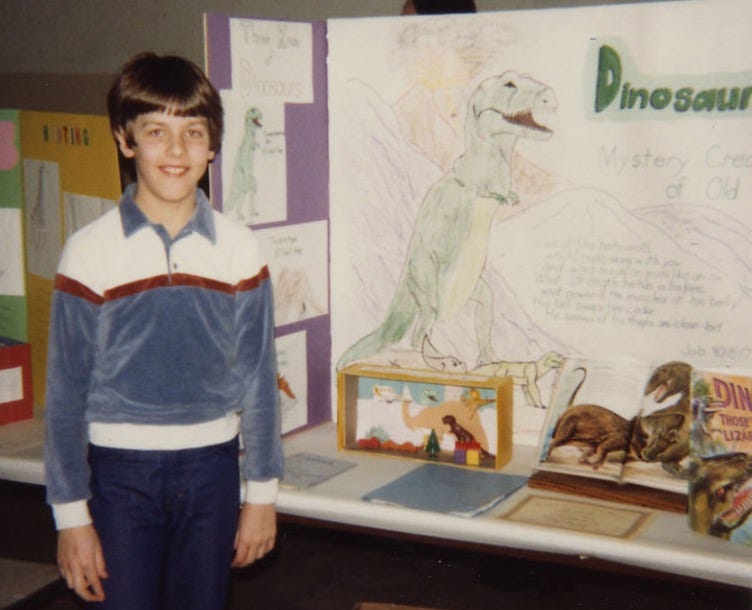

In many ways, I was like any other kid: Pictures of dinosaurs based on skeletal remains and fossils fascinated me. I loved drawing my personal favorites—T-Rex, of course, but Triceratops too. I even made dinosaurs the focus of my 6th-grade school report, “Dinosaurs: Mystery Creatures of Old!”, complete with hand-drawn mural and diorama!

I wanted to believe that the world had such a rich history of monsters. But, as with so many of my childhood passions, my enthusiasm for dinosaurs stressed me out. I was always anxious that I might be failing some kind of test posed to me by God. In the conservative-evangelical Christian bubble of my childhood, I was surrounded by warnings that the accounts of earth’s early days in the book of Genesis were as literal as any newspaper reporting. Rampant biblical illiteracy led real human beings—adults! with real brains! in positions of leadership!—to conclude that God had made the world like magic in just six days, and that nothing had existed on this planet more than 6,000 years ago.

So, what could it mean if we found fossils and dinosaur bones in the strata of the earth that suggested the planet was older than that? It was a trick! Someone—perhaps God himself!—might have planted such mysteries in the soil as a test: How strong was our faith in the Bible? Would we choose to believe God’s Word, or would we fall for a conspiracy?

I remember suffering such a deep disillusionment because of this popular perspective. I wanted to believe that dinosaurs existed. I wanted to think of the earth as a vast reservoir of secrets just waiting to be discovered, secrets that would, when brought into the light, amaze me and increase my sense of awe and reverence for the world. Instead, the world came to seem like an extraordinarily cruel conspiracy, carefully calibrated to threaten me and my small community.

Thank goodness (which is to say, thank God!), wiser teachers intervened. These were adults who did not feel threatened by complexity, by ambiguity, by mystery. They studied the Bible without any interest in discrediting it. Rather, they wanted to understand it—what it is, how it came to be, what different genres are represented within it, and how those genres are best understood. They understood that the Genesis account is written in a tradition of poetic narratives, drawing upon pre-existing narratives and revising them in order to establish an understanding of a benevolent and gracious creator, one who loves the world. They taught that Genesis communicates through the richness of art rather than claiming to offer a merely factual record. They helped me see that those who insist on a literal interpretation are ignoring all kinds of history—especially the history of the church itself, and the Judaic traditions of interpreting and understanding what Christians tend to call “the Old Testament.”

Teachers and scholars have understood the nuances of the many genres represented in the collection of texts we now call the Bible since long before Protestantism’s sudden shift to narrow literalism, a trend that gained momentum as a fearful reaction to the Enlightenment. When scientists began discovering that the cosmos is so much grander and more complicated than we ever imagined, it upset a lot of people—Christians included. They needed to believe that Planet Earth was the center of the universe, and that the sun revolved around us instead of the other way around. If science suggested that the Bible didn’t contain the answers to all of our questions, wasn’t it a threat to Christian faith? My good teachers reassured me: The Bible can equip us to become discerning about the questions we encounter in the world, but it makes no claims about itself as an answer to every question. How can it? It’s a collection of texts spanning multiple genres written by many different authors for many different purposes over many years. (Moreover, what texts end up in that final collection is a matter of substantial debate across Christendom!)

These teachers gradually convinced me that God was not playing a mean game of “Gotcha!” They taught me that creation is full of wonders, and that the strata of the earth are pages in which we can explore God’s mysteries just as we explore them in those poetic and profound narratives of the Old Testament, stories that enabled the Hebrews to distinguish the god they believed in from the gods of other cultures.

They gave me back a belief that God is still a creator, still working out an incomplete narrative, and that the world is a site of constant change. But they also helped me come to appreciate that God is up to something particularly fascinating in the existence of human beings who have the capacity to love the whole world, to serve a greater good, and to do so with joy and creativity. Unlike other species, we seem aware of, and capable of collaborating with, God’s creative endeavors—which we do whenever we practice the love we see evident in God’s work.

In short, those teachers gave me back my dinosaurs.

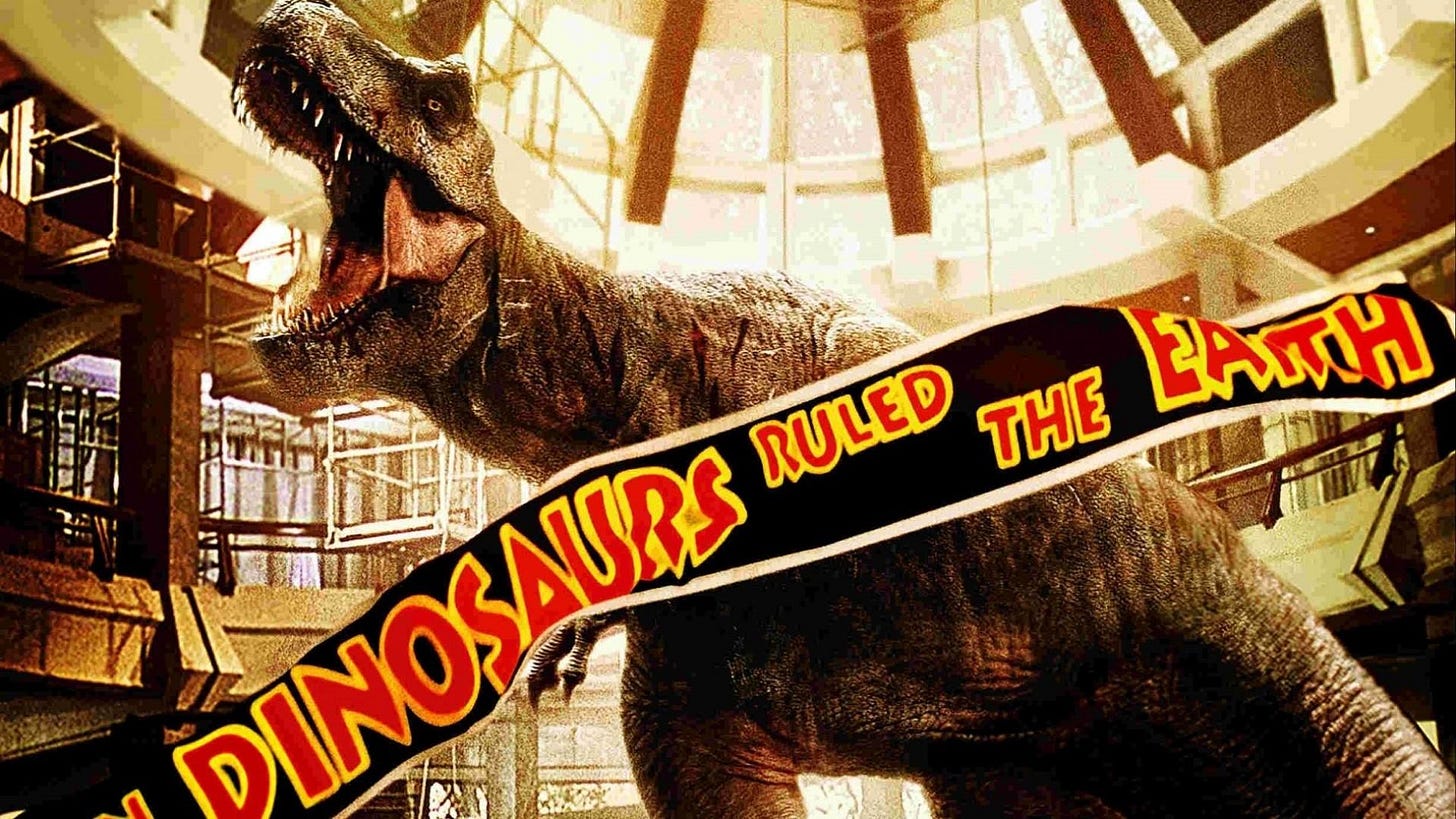

If Jurassic Park had opened when I was seven, I would have felt as if Steven Spielberg was an agent of the devil sent to threaten my faith. As it is, I appreciate Spielberg’s original film as a celebration of human curiosity, an expression of love and awe for certain aspects of the natural world, and a profound cautionary tale about what happens when human beings become too arrogant, eager to show off their power without thinking about the consequences in the world around us. As Jeff Goldblum’s Ian Malcolm famously laments, the Jurassic Park scientists were “so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn't stop to think if they should.” And thus, a deadly menace was unleashed upon the world.

How about that? A mainstream entertainment that teaches the importance of considering the greater good! A “secular” movie that inclines us all to revere God’s creation with humility, discipline, and awe, and that urges us to use our gifts responsibly for the greater flourishing of the world!

As it is, I saw Jurassic Park on opening weekend on Seattle’s panoramic Cinerama screen, and I have vivid memories of laughing in amazement and watching both the movie and my friends’ giddy terror as the T-Rex stormed across the screen for the first time.

I loved Spielberg’s original film from that first encounter — but never without qualifications.

Most of all, I loved the astonishing spectacle of dinosaurs—dinosaurs that looked and sounded alive and active and dangerous. That sixth-grade student I was in 1982 had never dreamed he would see a T-Rex as lifelike as this one.

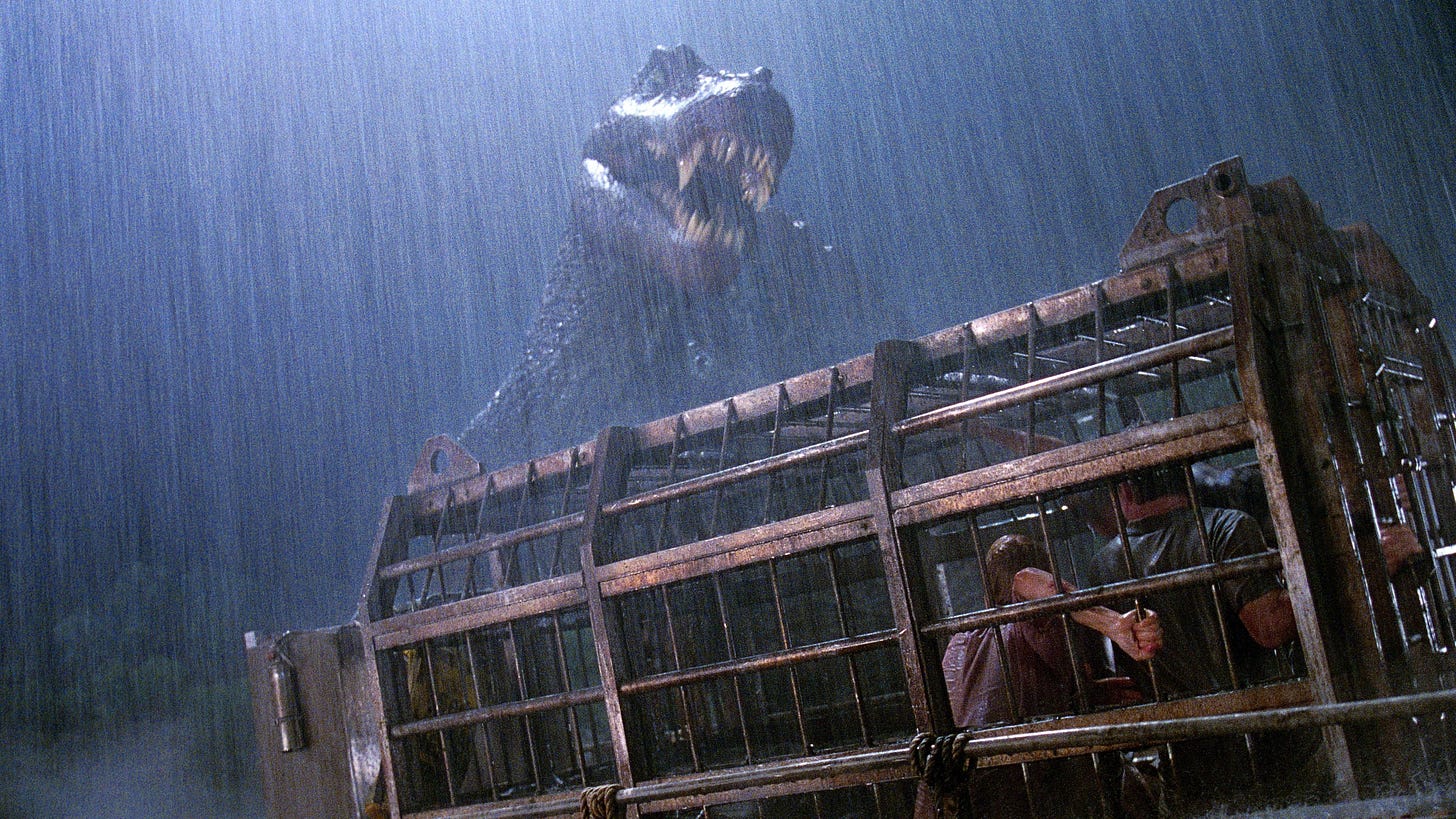

The incorporation of digital animation and practical effects in Jurassic Park remains, for me, the gold standard of such work in the history of adventure filmmaking. I believe what I’m seeing in almost all of the scenes involving dinosaurs. And I love the important lessons about hubris and folly learned the hard way by the park’s designer, poor John Hammond (Richard Attenborough), playing what appears to be a reckless and misguided version of his brother David that the film so effectively illustrates).

But Jurassic Park has always felt much more like a shiny commercial product for me than the five films that established Spielberg as the most influential filmmaker of my childhood and adolescence. While I grew up obsessed with Disney animation, the Muppets, Star Wars, and Watership Down, Spielberg’s films of the ’70s and ’80s were my elementary-level film school. I believed in the worlds of Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, and Empire of the Sun so much more than I believed in Jurassic Park. The people in those movies seemed real, complicated, unpredictable. These were grittier, more experimental, more nuanced, more human movies.

And he wasn’t done with films like that. He directed Schindler’s List simultaneously with Jurassic Park, a fact that still blows my mind. And none of the Jurassic characters have that fully-human complexity that the characters in his earlier genre films do. The characters of Alan Grant (Sam Neill), Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern), Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), and the rest, while engaging and funny, feel more focused on entertainment and less on authenticity.

John Williams’s score has a familiar bombast and lush romanticism, but it lacks the complexities and ambiguities of his best work.

And the finale? It lacks the thrilling intensity of the film’s best sequences—the T-Rex’s attack on the heroes during a rainstorm, the raptors’ stalking the heroes indoors.

Sequels? They only accelerated my disappointment at just how far short of its potential this franchise was falling. Just as each Indiana Jones sequel has fallen farther from the high standard set by the first film, none of the Jurassic sequels rate anywhere close to the original for me. They seem desperate. Derivative. Dumb as a bag of dying flashlights. It’s as if they’re trying so hard to recapture the magic of the original by imitating it that they cannot be bothered to invest in the only work that could, actually, achieve a similar impact: bold creativity. That is to say, they do not take risks. They have little or no curiosity in expanding the scope of what these movies might be about, or what kinds of stories might be told in that world.

There are moments in Jurassic Park III that rekindle some of the enchantment and awe I felt watching the original, but that’s due to Joe Johnston’s rowdy irreverence, his way of making us feel the stakes for the characters in peril, and some moments of aesthetically enthralling imagination. (The memory of a pterodactyl stalking a character on a bridge in the fog still gives me chills.)

Reviews of the last film, Jurassic World: Dominion, were so poor even among the franchise’s biggest fans that I haven’t bothered to see it.

Over three decades, we have come to a place where any reference to the Jurassic franchise does more to stir up my frustrations and disillusionment with franchise filmmaking than it does to remind me of that exciting first film. It’s going to take a remarkable artist to make a movie screen rekindle my any of my childhood fascination for dinosaurs.

And Gareth Edwards, no doubt burdened by all kinds of studio restrictions regarding what he can and cannot do with a franchise property, has his work cut out for him trying to make that happen.

So, here were are: It’s time for my notes on Jurassic World Rebirth.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Give Me Some Light to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.