Fundamentals of Fatherhood: Reflections on My Father's Life (in Four Parts)

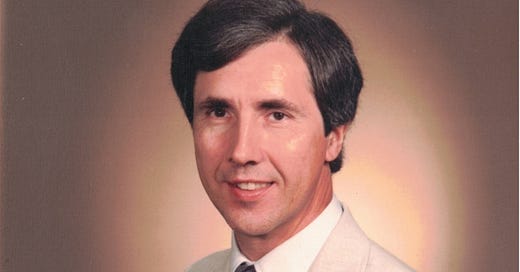

I offered a much-abridged version of these reflections at the Celebration of Life service in memory of my father, Larry Overstreet, at Damascus Community Church on Saturday, June 21.

I offered these words at the beginning of my father's Celebration of Life at Damascus Community Church on June 21. I share them here — the original, unabridged draft (which I had to cut back considerably at the event, as we were pressed for time).

First, though, I offer my deep gratitude for all who attended the service; your presence meant so much to my mother Lois, my brother Jason and his family, and Anne and me.

Thank you.

Dad, this is for you.

Jeffrey

Fundamentals of Fatherhood:

A Son's Remembrance

My job this afternoon is to offer the testimony of a son — one of two. The second son's testimony is one you will receive as music (arguably a language more transcendent) —from Jason, accompanied by Marisa and Levi, of course.

If I seem to speak as much or more of God than of Dad, that’s because he instructed me to. He wanted me to talk about, in his words, “the full measure of God’s faithfulness.” The full measure. We don't have nearly enough time for that! Dad, if you're listening, you'll know by now that any details that I share about you are, truly, a testimony about God’s faithfulness and love, which are beyond any measure.

Part One: The Practice of Fundamentals

As you can see here [I gesture to furniture set up to my left on the platform] — we have some of what we might call The Larry Overstreet Fundamentals.

The Chair: This is the actual chair where he spent many years of his life marinating in the Word of God and in books about the Word of God.

The Books: On the book table, there were always several books within reach — books by theologians, Biblical scholars, and pastors (he was especially fond of Seattle Pacific alumnus Eugene Peterson), but also books by journalists and memoirists like the great Philip Yancey, and the spiritual writer and poet Scott Cairns. Often, he would put on a show-and-tell of new books before I could take off my coat, before he had locked the front door behind me.

The Fireplace: They wouldn't let us bring his beloved wood stove into the church, or light a fire here, for obvious reasons! You can use your imagine for that. He loved that stove, one he expertly fed and took pride and pleasure in.

It’s an art, building a fire. It's an act of faith — there are no guarantees. But if you master the fundamentals — if you do things carefully, in a certain order, with quality materials — then, with a puff of breath and the strike of a match, a spark can grow into flames. These flames are a comfort, light and heat through hard winters, comfort through seasons of doubt and loss.

Today, as briefly as a novelist can (forgive me), I’ll share some of the fundamentals of my father’s life. I pray that the Spirit moves, a breath that will set this humble kindling to light. I hope we are all comforted. And illuminated.

When his sons remember their father, they inevitably think of his focus on the fundamentals.

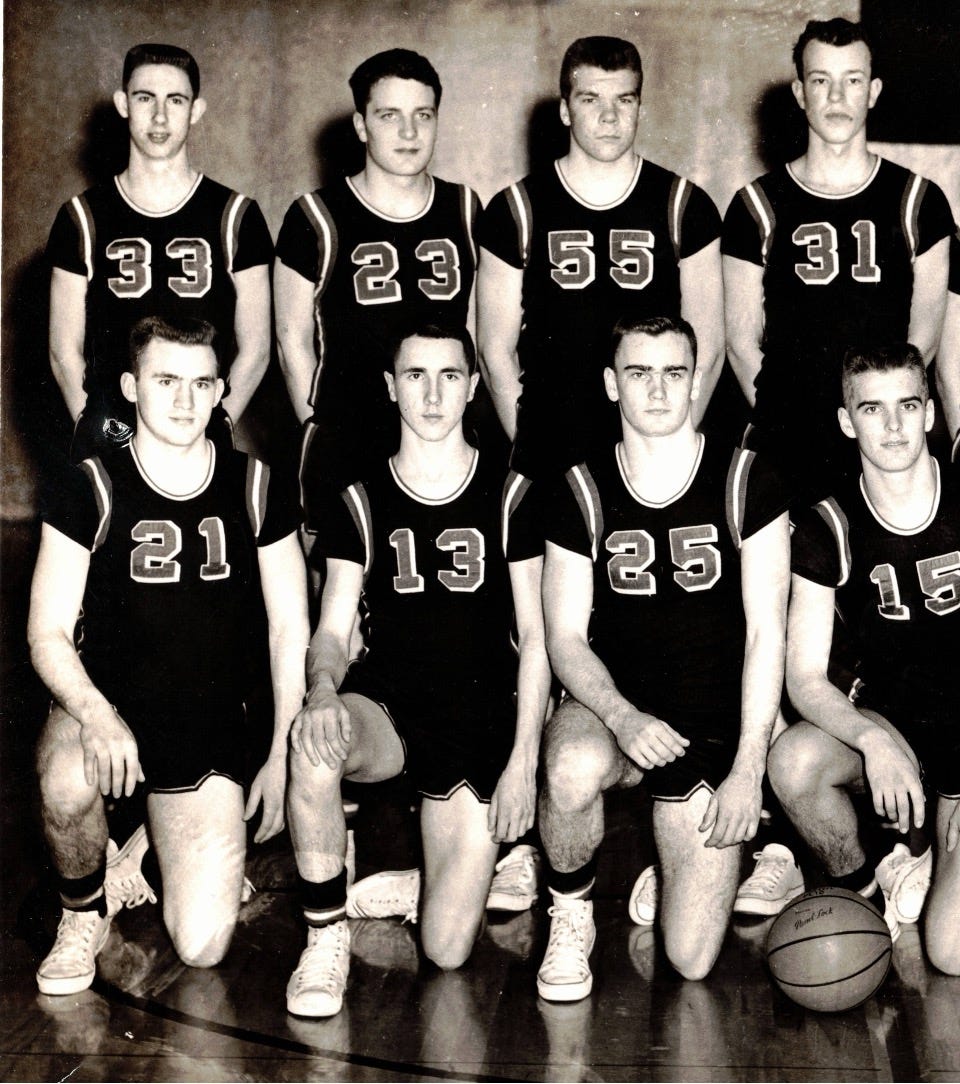

Dad taught us the fundamentals of free throws:

Balance

Elbows properly aligned.

Eyes on the back of the hoop.

And, as important as anything else: the follow-through. Your shooting hand gracefully completes the arc of the motion. Dad explained that this final flourish is not just because it looks good. It’s because you’ll take a better shot if you’re thinking about that last part. Even though the ball has already left your hands, by thinking ahead to that smooth finish, you give the shot a more graceful arc.

This guidance would be tested on Portland Christian basketball teams in the rigors of Rich Remsburg’s coaching. And — and I remember thinking, “Wow. Dad was right! He knows what he’s talking about!”

These are important moments, when what your parents teach you is tested in the world and it holds up. And Dad taught us plenty of solid fundamentals:

Lawn mowing had fundamentals (especially since our mower had a long orange cord that needed to be kept out of the way). Leaf-raking. Gathering fallen apples. Walking had fundamentals: whether around the neighborhood, the golf course, or the beach, you need good shoes.

The fundamentals of marriage — Dad and Mom modeled that for us every day.

The fundamentals of fatherhood? Faith, hope, and love. At church, at school, at home. Togetherness. He did his homework, so we did ours. He gathered us for evening devotions and prayers.

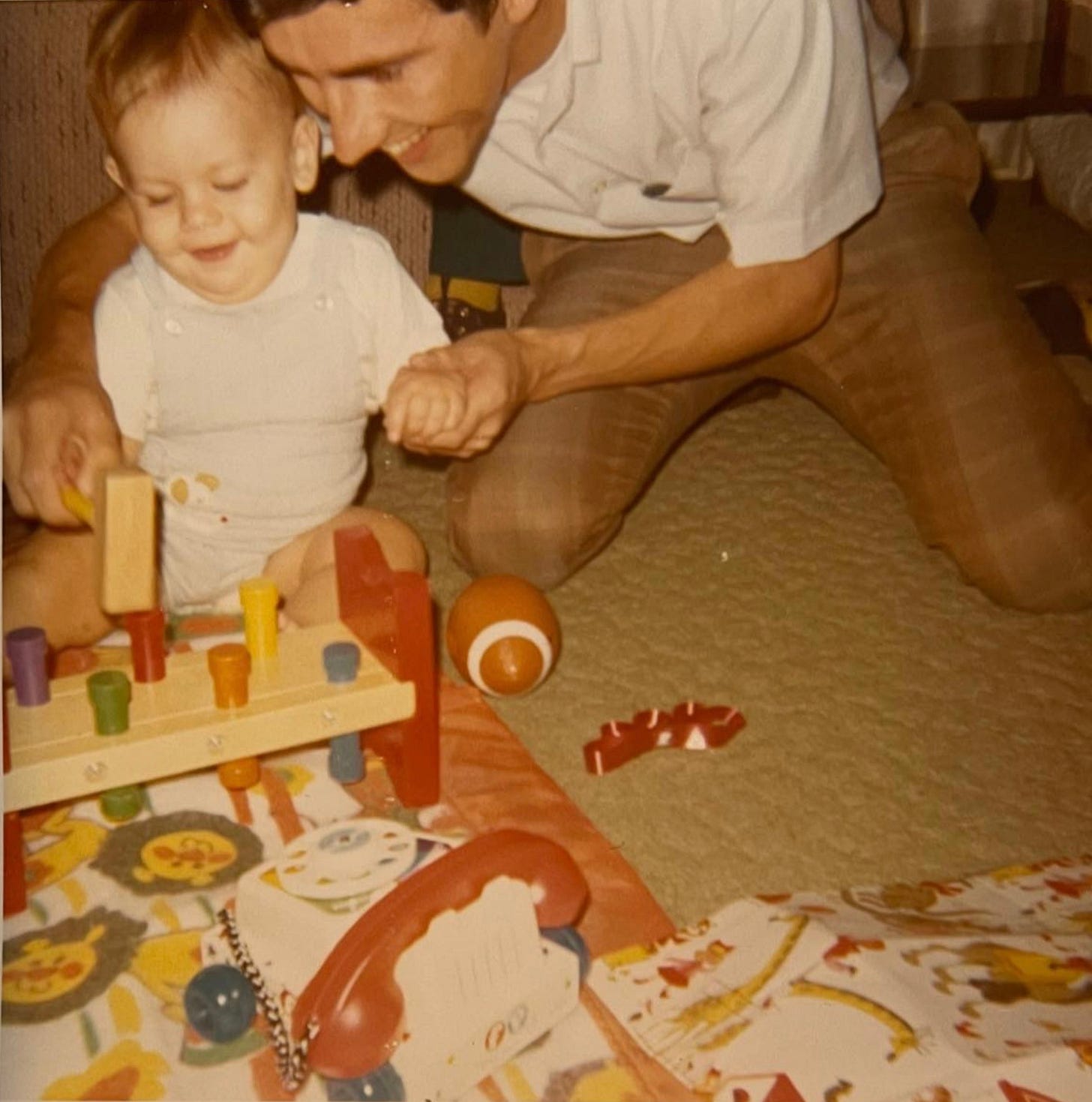

And play. Dad loved to play. You’ll see for yourself, in today’s slide show (curated by my mother), just how many pictures we have of delighting in play — with me, with Jason, with his four grandchildren. And you’re seeing about half of pictures Mom wanted to show you! We could show you pictures of Dad at play all day.

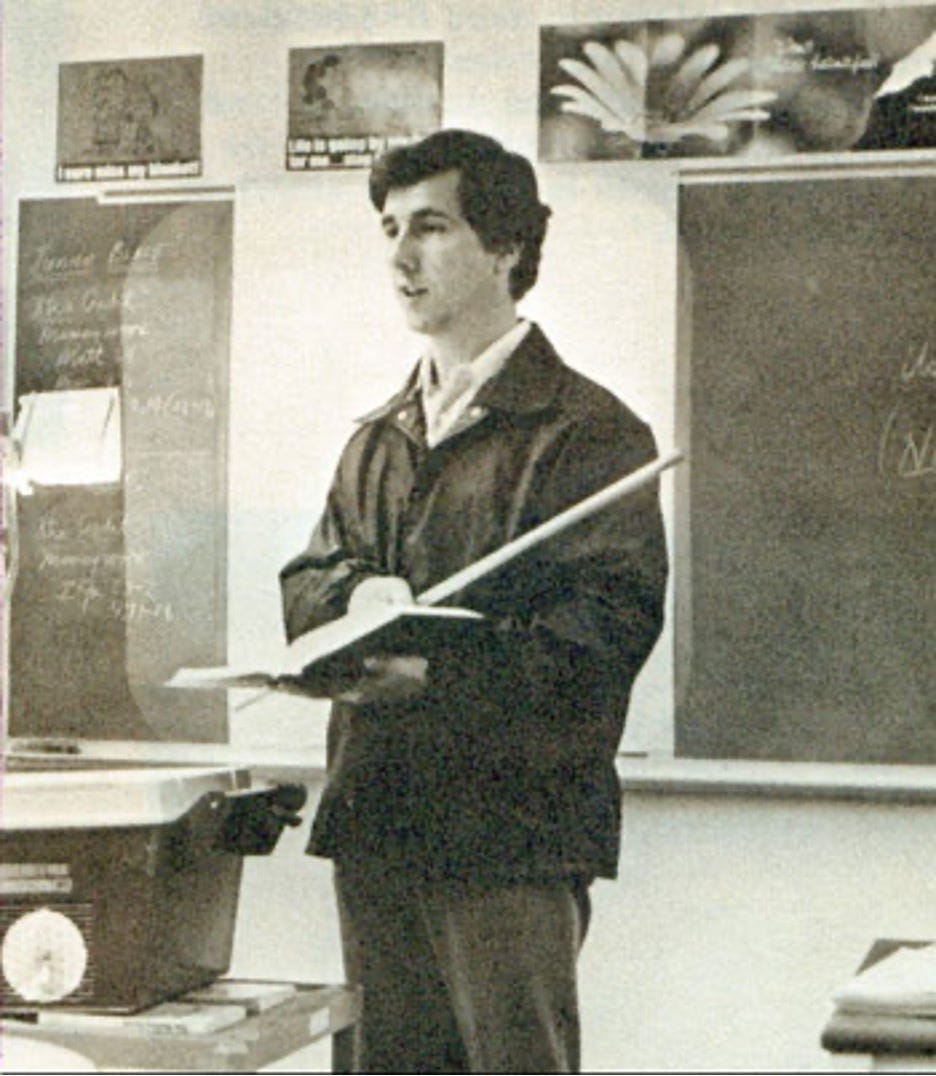

So, Jason and I understood the importance of fundamentals — even if the fundamentals we practiced would end up being different than his. Me? I found my sense of purpose and my experience of God in creative writing and in the experience of music and movies. Jason found his in musical composition, production, and performance. But both of us experience in our occasions of teaching the same sense of God’s presence that Dad did. It’s not the thrill of being up in front of people — it’s about the joy of having an opportunity to imitate and testify to the glory of God in our particular arts.

Most importantly, Jason and I absorbed Dad’s emphasis on the fundamentals of faith:

Prayer — not just before meals (although there, always, yes), but in times of trouble and times of celebration.

Studying the Scriptures and studying scholarly interpretations of them, so that we would understand them in context, appreciating the challenges of translation. Dad was as faithful to reading, note-taking, and reflecting as to any other discipline — perhaps more so.

His passion to understand the Bible was so intense that it was contagious. Here’s what rebellion looked like for me: I would stay up past my bedtime with my clock radio tucked under my pillow so that, while Mom and Dad thought I was asleep, I was listening — not to music, not to sports, but to Chuck Swindoll’s sermons on Insight for Living. The excitement I have in sharing texts with my students, sharing movies and music on my websites, that clearly came from his zeal for sharing whatever theological text he had just opened.

I cannot imagine how many times Dad, with the guidance of scholars, read through the whole Bible. So many of the writers he loved and recommended changed my life and my faith.

Philip Yancey’s What’s So Amazing About Grace? showed me that what sets Christianity apart from other religion is that Jesus favors Grace. Whenever religious leaders pointed accusing fingers at sinners, Jesus stepped between them and the accused and favored grace over judgment.

Yancey’s The Bible Jesus Read taught me to pay close attention to the genres of the Old Testament, and to understand how prophecy is poetry.

Reality and the Vision, a book Dad gave me as a graduation gift, was written by a collection of Christian writers called The Chrysostom Society—including Philip Yancey, Madeleine L’Engle, Luci Shaw, and Eugene Peterson. Each one wrote about a writer who inspired their imagination and their faith. Some of the writers they praised were fiction writers and poets. Some were not even religious—this made an impression on me, to practice finding God’s wisdom at work outside of Christian books.

Reading was not just work for Dad. It was joy. Reading became important to me because I saw how he loved it. Writing became important, too, because I wanted to do work that as worthy of his attention. (He never became a fiction reader, though I’m grateful he gave my stories a try.)

David Dark, a writer I recommended to my father, might as well be writing about Dad when he says this:

The texts that get called scriptures by various religious traditions are often used by individuals (mostly quoted out of context) to pepper speeches, buttress bad arguments, and, on occasion, to avoid awareness of responsibility for our actions. We read and quote selectively to better justify what we’ve already decided to do. Where is the self-awareness in any of this, the sense that our scriptures can, and should, change the way we think and act?

…

Are we up for a redeeming word?

...

We only receive [the Scriptures] when we let it call our own lives into question. If the words of Jesus of Nazareth ... strike us as comfortable and perfectly in tune with our own confident common sense, our likes and dislikes, our budgets, and our actions toward strangers and foreigners, then receiving the words of Jesus is probably not what we’re doing. We may quote a verse, put it in a PowerPoint presentation, or even intone it loudly with an emotional, choked-up quiver, but if it doesn’t scandalize or bother us, challenging our already-made-up minds, we aren’t really receiving it.

Part Two: The Priority of Grace

I came to understand that my father’s practice was like the Jewish rabbinic of midrash of creatively exploring to discover new insights in a familiar sacred text. One of Dad’s favorites showed me how, if you keep revisiting the Scriptures, your understand will keep expanding and deepening. That book is Tim Keller’s The Prodigal God.

I grew up thinking that Jesus’ parable of the Prodigal Son had a simple lesson: Don’t be a bad son. Don’t disrespect your father and mother. Don’t squander your inheritance. Be obedient. Don’t break the rules.

In time, though, I came to appreciate how the Prodigal's Father in the story is wildly generous. Have you ever noticed that we never hear the prodigal son apologize? That’s because the father gives grace so fast that the son never has a chance to ask for mercy. I could see my father in that Godly father.

What I’m about to say is not always true — but my experience has taught me that it is often, perhaps even commonly, true: Men I have known who have struggled to believe in a loving God often did not have a loving, tender, gracious, faithful father. Men I’ve known for whom such faith has come more easily, their fathers have almost always been loving, tender, gracious, and faithful, without being legalistic or judgmental.

My father led with grace.

When I disappointed him by quitting basketball in order to invest more fully in the solitary pursuit of writing fiction — a genre I never saw him reading, a kind of writing it would be hard to find in his collection — he offered me nothing but support.

When I ran up a $450 long-distance phone bill in college on my parents’ dime, he forgave. When my first marriage failed, I heard no judgment from him; only grace.

Jason wants me to share two stories. He says, “One of my biggest memories of my dad was when I totaled his new truck just months after getting my license. I remember sitting on the sidewalk by the Kmart on 122nd and Sandy, completely distraught about what I had done. When he arrived, he didn’t say one word about the truck, but was only concerned with that I was okay, and how I was doing. This is just one example of his unending grace and love.”

Another story from Jason: “I also remember when I bought a new car straight out of college. He didn’t judge me… or at least, never outwardly said anything… but I soon learned the hard way that it isn’t fun to be ‘car broke’. He probably thought it, but never said ‘I could have told you that.’ These are just a couple of examples of his unending grace and love.”

Faith is a work of imagination, and imagination is strengthened by examples. My father was an example of a humble son at his father’s feet. He was an example of a father who values grace over pride or power. In his humility and generosity, he gave us a definition of godliness strikingly different from the harmful models of masculinity often exalted in the world—and too often exalted in evangelical culture.

But Keller’s book wasn’t done with me yet. I wanted to be known as “a good son.” But these days, I think most often about the character who did not run away, who followed the rules, who seemingly did everything right. The Good Son. Keller told me to pay attention to the scene at the end of the story, the scene that was often left out of Sunday school versions, the scene I had never really liked. When the Good Son learns of his father’s grace for the Prodigal Son, he is offended. He insists that such celebrations should be earned. He insists that the son who follows the rules should get the privileges. Good citizens. Good believers. But notice: This son does not have his father’s capacity for joy, for celebration, for generosity, for grace. For the Good Son, those who don’t measure up don’t get handouts. They should not be embraced and blessed.

The Good Son — he had learned the fundamentals. But he had turned them into a new law, a law by which he would measure and judge others. Believing in fundamentals without grace, he had become a fundamentalist.

That is not the father’s nature. It was not our father’s nature.

The Prodigal’s Father says this to the Good Son (and I’m paraphrasing): “You already have all of these good things that I’m sharing now with your brother. It was never about earning them. Another of my children is here — the one you perceive as less worthy than you — in your worldview based on righteousness over grace.”

At the end of the story, there is still an empty seat at the father’s table. So, Keller asks us, Who is the prodigal son at the end of the story?

Larry Overstreet lived in gratitude because he had experienced God’s grace. He lived in a state of wonder about that. And because of that, he found joy in extending that generosity to others: family, neighbors, and even, in his last year, hospital staff.

If the Bible is clear about anything, it is clear about how our claims to faith and righteousness are true only insofar as we rejoice in, and practice, God’s generous love for our neighbors — particularly the poor, the stranger, the immigrant, the refugee, and those who discomfort or offend us with their choices and beliefs. Our neighbors. All over the world.

Part Three: The Faithfulness in Suffering

Here’s the challenge: You can do everything right. You can follow the rules. You can be gracious and generous. But the fundamentals will not shield you from suffering. Your plans will be disappointed. Things you took for granted will fail you. A free-throw with perfect form might miss. You can be a master in writing or in music and still find that the work falls flat or no one responds to it. You can love your career, and it can be taken from you suddenly. Even the best at an art or a discipline may not find, by the world’s definition, success. Even the best-built fires get blown out or flooded by hard weather.

Hard weather, in the experience of the Overstreets, comes sometimes in the form of depression. Depression is not necessarily the fault of the one who suffers: It can be a consequence of chemical imbalances, of past abuse, of things experienced by previous generations you might not even know about. Jason and I both have some experience with it — and not for any lack of love and care from our family.

Dad struggled with depression. I could feel it in the house when I was a teenager. I remember how cold winds blew out his capacity for teaching for a time. I didn’t understand what was happening. It scared me.

His journey through different jobs after teaching was often frustrating and unsatisfying. But it felt like there was something heavier weighing on him. And it worsened with the onset of his hearing loss. He described “a rapidly shrinking world.” He wrote in a draft of his own life story, “Feeling stuck in my personal, vocational, and ministry life, I could no longer engage in my usual ways in public gatherings, interactive classes, small groups, and church leadership, teaching, and worship activities.” And, he added he could no longer “enjoy most musical harmony and melody.” He attended my brother’s concerts, but it grieved him that he could not hear them anymore.

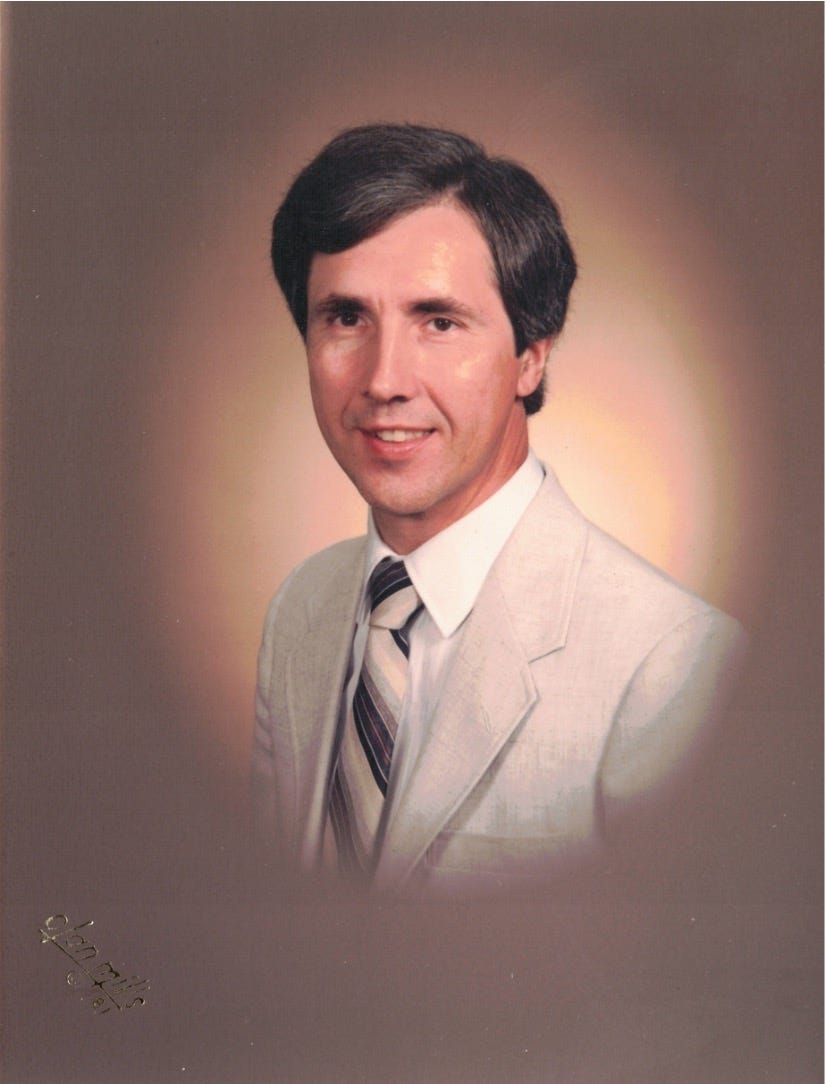

Sensing that my opportunities for close communion with Dad were rapidly diminishing, I invited him, in 2018, to spend a day driving me around Mossyrock and Chehalis, Washington, where he’d grown up. (He was born in Chehalis on March 8, 1944.) We explored some of the surrounding areas where he had gone fishing, where his father had built houses (that are still occupied!), where he had gone to school. I recorded a lot of audio and video that day, and took a lot of photos. And I’m so glad. He opened up about things he’d never told me about before.

As we sat at the edge of the cemetery where his parents were laid to rest, he named — at last! — the shadows I had felt.

Dad’s own father, Glen Overstreet, was a generous home builder — one who rarely charged his customers what he should have. Glen forgave debts. He sacrificed to give people breaks. (My father was that way too. The enormous discipleship guide he was writing over the last ten years of his life was a project he intended to give to the world free of charge.) Because of his own father’s extravagant, even exasperating, generosity, the Overstreet family struggled financially. Then, Glen started suffering neurological disruptions. It’s very likely that he had brain cancer like the kind that struck my father. Glen was worried he would ruin his family with the medical costs that would surely come. In 1966, he made a tragic decision. Dad received the news of his father’s sudden death while he was a student at Seattle Pacific. It a devastating blow. He took time off from school. And just five years later, his beloved Uncle Warren passed as well, making the same terrible choice.

When I heard this, it was as if I had been given a lens through which I could see my own childhood — and my father — clearly for the first time. I understood the cold void I had felt in our house. And I could appreciate how Dad sought counseling through his trouble. I could admire the determination in his faithfulness. And I could see the influence of his faith as he fought some of the same dragons his father and uncle had faced.

During those long, heavy seasons, Dad’s story might have ended very differently. And the struggle was often intense. In his darkest hours of cancer, as his memories, his ability to read, and just about everything he enjoyed was taken from him, he would struggle to speak. And he would say, “All gone. All gone. All the words. The stories. The verses. All gone.” But sometimes, he would put his hand over his heart and add, “Most important things, still here. Still here. I still have that.”

I believe that my father’s fundamentals, a practice made possible by God’s grace, taught him to keep building fires of faith in new ways, from new materials, as conditions changed. As the great Wendell Berry writes in his essay Poetry and Marriage, “It may be that when we no longer know what to do we have come to our real work and that when we no longer know which way to go we have begun our real journey. The mind that is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.”

Dad drew courage from Second Corinthians 12: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” He pointed to Isaiah 26:3: “He will keep in perfect peace all those who trust in him, whose thoughts turn often to the Lord!” And he loved Isaiah 64:4: “For since the world began, no one has seen or heard of such a God as ours, who works for those who wait for him!” These passages kindled creativity. And he left us these words: “Private times of Bible reading, prayer and worship, and self-talking reflections often centered on these Spirit-guided reminders, greatly renewing my sense of ‘resting’ on God's reassuring presence and ‘waiting’ upon his promised guidance.”

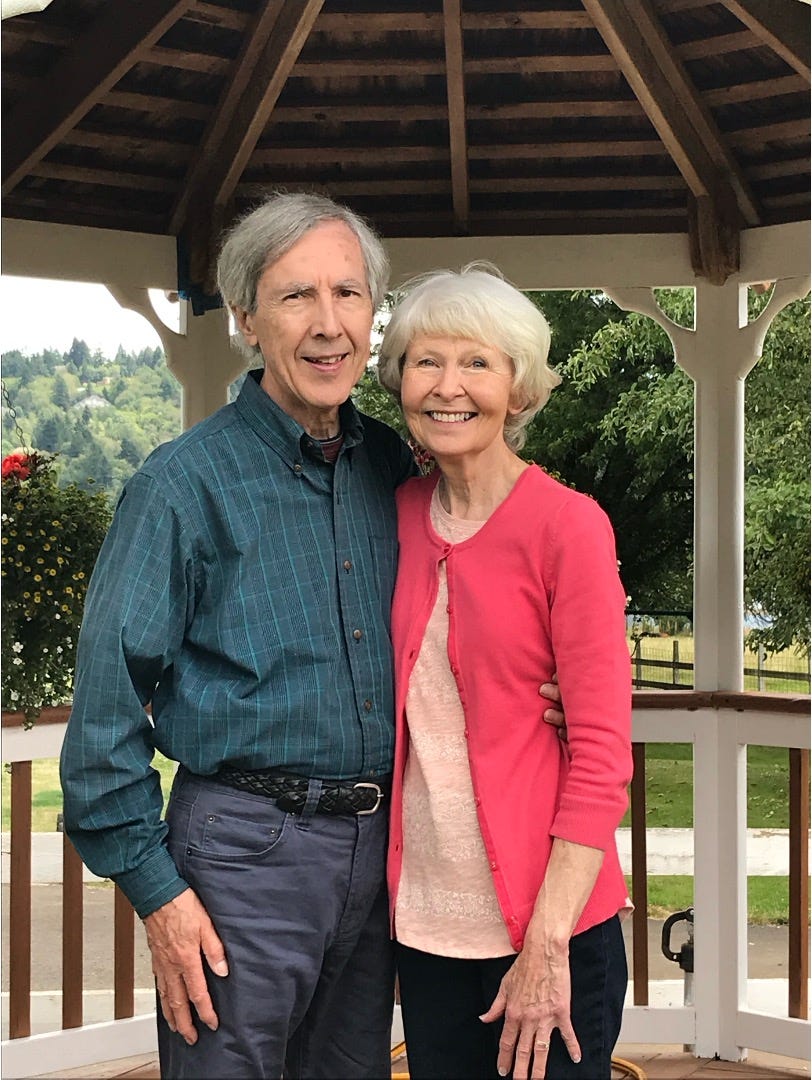

God’s greatest gift of grace for my father was, of course, my mother, who has been at his side caring for him all through these long years of hardship. They met at Seattle Pacific College just after his own father’s death. Lois Rydman’s radiance, and the loving and generous Rydman family who welcomed him, must have seemed like a sign of heaven on earth for him in the wake of such loss. All of us here have been witness to their love for each other, their faithfulness to each other, through the good days and the hardest of times.

At Seattle Pacific, they read a book called The Taste of New Wine: a book about learning that the Gospel is relevant to an everchanging world, and that believers must be creative — we must be flexible, and avoid hardening into fundamentalism.

He could never have guessed — who could have? — that his unwavering faithfulness to me would mean that I have now taught on that very Seattle Pacific campus for a decade now. In fact, I’ve been working there for a quarter of a century, walking every day past the stained glass window of the chapel where he proposed to my mother, past the window of the ping-pong lounge where they had their first date.

In March 2008, Anne and I found ourselves sharing our writing with a small group of Christian writers: The Chrysostom Society. They’d been meeting and encouraging each other for 40 years at that point. I stood at a podium and looked at those gathered before me, and it was like looking into my father’s library. So many great minds who had blessed and guided both him and me were looking right back at me: Eugene Peterson. Luci Shaw. Scott Cairns. Eventually I would meet Philip Yancey, who still part of the community.

And when I called my father excitedly to tell him how they had invited me to minister to them, and then listed their names, one in particular shocked him. “Keith Miller!” I heard him say, “Honey! Jeff and Anne are with Keith Miller!” And so, on my next visit to Portland, I gave Dad and Mom a new copy of the book they had read in their courtship — A Taste of New Wine — with a long, personal message from the author. Keith wrote to them, “I hope that our paths will cross again soon.”

In a manner of speaking, their paths have converged at last.

Part Four: The Follow-Through

As he felt the end approaching, Dad began working on a project with Dr. Rick Calenburg, a way to bring his life of studying the Scriptures to fruition. He boxed up almost all of his beloved books and shipped them off to become a vital part of the collection of the Evangelical Seminary of West Africa in Liberia.

That took a great act of surrender, of selflessness, of vision for what would come after his departure. Who knows what his stewardship of those texts over so many years might go on to accomplish in hearts and minds of new believers, new teachers, new ministers and missionaries.

He was right, you see. The follow-through matters. It makes the effort beautiful. And if you have your eyes on a graceful finish, the whole work becomes more meaningful.

Swish.

Some things remained embedded in his heart. When he emerged from surgery, under the influence of those amazing drugs, all he wanted to tell the hospital staff about was my mother’s love for him and her amazing achievements in the art of soup-making. “Her soup,” he would tell them, over and over again, “is unbelievable. Unbelievable.”

His love for his children, his nieces, and his grandchildren remained. I will remember with gratitude that the last time I saw him smile and laugh was when my cousin Jenny walked into his hospital room and he recognized her.

This I believe: We will be reconciled with those we love. With those we have judged and disliked. If Jesus asks God to forgive even those who are murdering him and causing him that most excruciating and humiliating of deaths, do you think the God who “so loved the world” — this hard and wicked world — will ever close his arms to a soul, or that God will ever cease the work of reconciliation? I believe my father is testifying before the throne, testifying of the full measure of God’s faithfulness. And I can see Dad’s uncle and his father there with him, too. They are there listening to his testimony. They are joining the chorus. That’s because I dare to believe what the scriptures promise: that “every knee shall bow, every tongue confess, that Jesus is Lord.” We will be reunited with all we’ve thought we’ve lost. Our heavenly father, who will never condemn or exclude anyone who reaches for his love, will wipe every tear of loss and grief from our eyes.

On one of his last evenings at the hospital, Dad seemed to be asleep. He only had a few more days with us. I heard him humming a few notes, and this surprised me, as he had been unable to perceive music in so long. Mom said that this had been happening. We weren’t sure how conscious he was as he sang. But as I listened, I realized that he was singing the words of the Doxology. Was he awake? Was he aware? Does it matter? Those words — words he had sung with the congregation at every Gateway Baptist Church service for so many years of his life before he lost his hearing and had to withdraw — were still there. Deeply embedded. Written into the very heart of him.

And if we sing it together now, we are singing with him. We are practicing the fundamentals. And, by God’s grace, we are — as my father wanted us to do here and now — embedding these words in our own hearts:

Praise God from whom all blessings flow

Praise him, all creatures here below

Praise him above, ye heavenly hosts

Praise Father, Son and Holy Ghost.

Amen.

Until our paths cross again, Dad, thank you for everything. I love you. May the Lord bless you and keep you. May the Lord’s face shine upon you and give you peace.